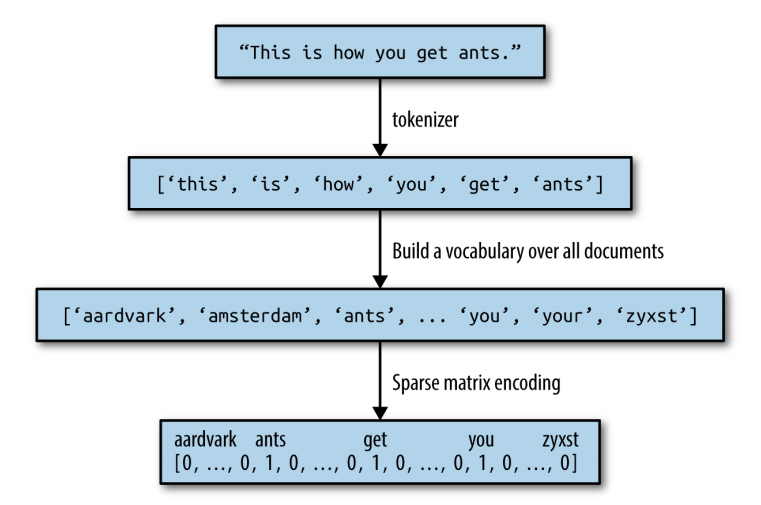

One of the most simple but effective and commonly used ways to represent text for machine learning is using the bag-of-words representation. When using this representation, we discard most of the structure of the input text, like chapters, paragraphs, sentences, and formatting, and only count how often each word appears in each text in the corpus. Discarding the structure and counting only word occurrences leads to the mental image of representing text as a “bag”.

Computing the bag-of-words representation for a corpus of documents consists of the following three steps:

- Tokenization. Split each document into the words that appear in it (called tokens), for example, by spliting them on whitespaces and punctuation.

- Vocabulary building. Collect a vocabulary of all words that appear in any of the documents, and number them (say, in alphabetical order).

- Encoding. For each document, count how often each of the words in the vocabulary appear in this document.

Figure above illustrates the process. The output is one vector of word counts for each document. For each word in the vocabulary, we have a count of how often it appears in each document. That means our numeric representation has one feature for each unique word in the whole dataset. Note how the order of the words in the original string is completely irrelevant to the bag-of-words feature representation.

Applying Bag-of-Words to a Toy Dataset

The bag-of-words representation is implemented in CountVectorizer, which is a transformer. Our toy dataset consists of two samples.

In:

bards_words =["The fool doth think he is wise,",

"but the wise man knows himself to be a fool"]

We import and instantiate the CountVectorizer and fit it to our toy data as follows:

In:

from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

vect = CountVectorizer()

vect.fit(bards_words)

Fitting the CountVectorizer consists of the tokenization of the training data and building of the vocabulary, which we can access as the vocabulary_ attribute:

In:

print("Vocabulary size: {}".format(len(vect.vocabulary_)))

print("Vocabulary content:\n {}".format(vect.vocabulary_))

Out:

Vocabulary size: 13

Vocabulary content:

{'the': 9, 'himself': 5, 'wise': 12, 'he': 4, 'doth': 2, 'to': 11, 'knows': 7,

'man': 8, 'fool': 3, 'is': 6, 'be': 0, 'think': 10, 'but': 1}

To create the bag-of-words representation for the training data, we call the transform method:

In:

bag_of_words = vect.transform(bards_words)

print("bag_of_words: {}".format(repr(bag_of_words)))

Out:

bag_of_words: <2x13 sparse matrix of type '<class 'numpy.int64'>'

with 16 stored elements in Compressed Sparse Row format>

The bag-of-words representation is stored in a SciPy sparse matrix that only stores the entries that are nonzero. The matrix is of shape 2×13, with one row for each of the two data points and one feature for each of the words in the vocabulary. A sparse matrix is used as most documents only contain a small subset of the words in the vocabulary, meaning most entries in the feature array are 0. Think about how many different words might appear in a movie review compared to all the words in the English language (which is what the vocabulary models). Storing all those zeros would be prohibitive, and a waste of memory. To look at the actual con‐ tent of the sparse matrix, we can convert it to a “dense” NumPy array (that also stores all the 0 entries) using the toarray method:

In:

print("Dense representation of bag_of_words:\n{}".format(

bag_of_words.toarray()))

Out:

Dense representation of bag_of_words:

[[0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1]

[1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1]]

We can see that the word counts for each word are either 0 or 1; neither of the two strings in bards_words contains a word twice.

Example Application: Bag-of-Words for Sentiment Analysis of Movie Reviews

For this example, we will use a dataset of movie reviews from the IMDB (Internet Movie Database) website collect by Standford researcher Andrew Maas. This dataset contains the text of the reviews, together with a label that indicates whetever a review is positive or negative. The IMDB website itself contains ratings from 1 to 10. To simplify the modeling, this annotation is summarized as a two-class classification dataset where reviews with a score of 6 or higher are labeled as positive, and the rest negative.

After unpacking the data, the dataset is provided as text files in two separate folders, one for the training data and one for the test data. Each of these in turn has two sub‐ folders, one called pos and one called neg.

data/aclImdb

│

├─── test

│ ├─ neg

│ └─ pos

│

└─── train

├─ neg

└─ pos

The pos folder contains all the positive reviews, each as a separate text file, and similarly for the neg folder.

In:

from sklearn.datasets import load_files

reviews_train = load_files("data/aclImdb/train/")

# load_files returns a bunch, containing training texts and training labels

text_train, y_train = reviews_train.data, reviews_train.target

print("type of text_train: {}".format(type(text_train)))

print("length of text_train: {}".format(len(text_train)))

print("text_train[1]:\n{}".format(text_train[1]))

Out:

type of text_train: <class 'list'> l

ength of text_train: 25000

text_train[1]:

b'Words can\'t describe how bad this movie is. I can\'t explain it by writing only.

You have too see it for yourself to get at grip of how horrible a movie really can

be. Not that I recommend you to do that. There are so many clich\xc3\xa9s, mistakes

(and all other negative things you can imagine) here that will just make you cry.

To start with the technical first, there are a LOT of mistakes regarding the

airplane. I won\'t list them here, but just mention the coloring of the plane.

They didn\'t even manage to show an airliner in the colors of a fictional airline,

but instead used a 747 painted in the original Boeing livery. Very bad. The plot

is stupid and has been done many times before, only much, much better. There are

so many ridiculous moments here that i lost count of it really early. Also, I was

on the bad guys\' side all the time in the movie, because the good guys were so

stupid. "Executive Decision" should without a doubt be you\'re choice over this

one, even the "Turbulence"-movies are better. In fact, every other movie in the

world is better than this one.'

The task we want to solve is as follows: given a review, we want to assign the label “positive” or “negative” based on the text content of the review. This is a standard binary classification task. However, the text data is not in a format that a machine learning model can handle. We need to convert the string representation of the text into a numeric representation that we can apply our machine learning algorithms to.

We loaded our training and test data from the IMDb reviews into lists of strings (text_train and text_test), which we will now process:

In:

vect = CountVectorizer().fit(text_train)

X_train = vect.transform(text_train)

print("X_train:\n{}".format(repr(X_train)))

Out:

X_train:

<25000x74849 sparse matrix of type '<class 'numpy.int64'>'

with 3431196 stored elements in Compressed Sparse Row format>

The shape of X_train, the bag-of-words representation of the training data, is 25,000×74,849, indicating that the vocabulary contains 74,849 entries. Again, the data is stored as a SciPy sparse matrix. Let’s look at the vocabulary in a bit more detail. Another way to access the vocabulary is using the get_feature_name method of the vectorizer, which returns a convenient list where each entry corresponds to one feature:

In:

feature_names = vect.get_feature_names()

print("Number of features: {}".format(len(feature_names)))

print("First 20 features:\n{}".format(feature_names[:20]))

print("Features 20010 to 20030:\n{}".format(feature_names[20010:20030]))

print("Every 2000th feature:\n{}".format(feature_names[::2000]))

Out:

Number of features: 74849

First 20 features:

['00', '000', '0000000000001', '00001', '00015', '000s', '001', '003830',

'006', '007', '0079', '0080', '0083', '0093638', '00am', '00pm', '00s',

'01', '01pm', '02']

Features 20010 to 20030:

['dratted', 'draub', 'draught', 'draughts', 'draughtswoman', 'draw', 'drawback',

'drawbacks', 'drawer', 'drawers', 'drawing', 'drawings', 'drawl',

'drawled', 'drawling', 'drawn', 'draws', 'draza', 'dre', 'drea']

Every 2000th feature:

['00', 'aesir', 'aquarian', 'barking', 'blustering', 'bête', 'chicanery',

'condensing', 'cunning', 'detox', 'draper', 'enshrined', 'favorit', 'freezer',

'goldman', 'hasan', 'huitieme', 'intelligible', 'kantrowitz', 'lawful',

'maars', 'megalunged', 'mostey', 'norrland', 'padilla', 'pincher',

'promisingly', 'receptionist', 'rivals', 'schnaas', 'shunning', 'sparse',

'subset', 'temptations', 'treatises', 'unproven', 'walkman', 'xylophonist']

As you can see, possibly a bit surprisingly, the first 10 entries in the vocabulary are all numbers. All these numbers appear somewhere in the reviews, and are therefore extracted as words. Most of these numbers don’t have any immediate semantic meaning — apart from “007”, which in the particular context of movies is likely to refer to the James Bond character. Weeding out the meaningful from the nonmeaningful “words” is sometimes tricky. Looking further along in the vocabulary, we find a collection of English words starting with “dra”. You might notice that for “draught”, “drawback”, and “drawer” both the singular and plural forms are contained in the vocabulary as distinct words. These words have very closely related semantic meanings, and counting them as different words, corresponding to different features, might not be ideal.

Before we try to improve our feature extraction, let’s obtain a quantitative measure of performance by actually building a classifier. We have the training labels stored in y_train and the bag-of-words representation of the training data in X_train, so we can train a classifier on this data. For high-dimensional, sparse data like this, linear models like LogisticRegression often work best.

In:

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

scores = cross_val_score(LogisticRegression(), X_train, y_train, cv=5)

print("Mean cross-validation accuracy: {:.2f}".format(np.mean(scores)))

Out:

Mean cross-validation accuracy: 0.88

We obtain a mean cross-validation score of 88%, which indicates reasonable performance for a balanced binary classification task. We know that LogisticRegression has a regularization parameter, C, which we can tune via cross-validation:

In:

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

param_grid = {'C': [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10]}

grid = GridSearchCV(LogisticRegression(), param_grid, cv=5)

grid.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Best cross-validation score: {:.2f}".format(grid.best_score_))

print("Best parameters: ", grid.best_params_)

Out:

Best cross-validation score: 0.89

Best parameters: {'C': 0.1}

We obtain a cross-validation score of 89% using C=0.1. We can now assess the generalization performance of this parameter setting on the test set:

In:

X_test = vect.transform(text_test)

print("{:.2f}".format(grid.score(X_test, y_test)))

Out:

0.88

Now, let’s see if we can improve the extraction of words. The CountVectorizer extracts tokens using a regular expression. By default, the regular expression that is used is “\b\w\w+\b”. If you are not familiar with regular expressions, this means it finds all sequences of characters that consist of at least two letters or numbers (\w) and that are separated by word boundaries (\b). It does not find single-letter words, and it splits up contractions like “doesn’t” or “bit.ly”, but it matches “h8ter” as a single word. The CountVectorizer then converts all words to lowercase characters, so that “soon”, “Soon”, and “sOon” all correspond to the same token (and therefore feature).

This simple mechanism works quite well in practice, but as we saw earlier, we get many uninformative features (like the numbers). One way to cut back on these is to only use tokens that appear in at least two documents (or at least five documents, and so on). A token that appears only in a single document is unlikely to appear in the test set and is therefore not helpful. We can set the minimum number of documents a token needs to appear in with the min_df parameter:

In:

vect = CountVectorizer(min_df=5).fit(text_train)

X_train = vect.transform(text_train)

print("X_train with min_df: {}".format(repr(X_train)))

Out:

X_train with min_df: <25000x27271 sparse matrix of type '<class 'numpy.int64'>'

with 3354014 stored elements in Compressed Sparse Row format>

By requiring at least five appearances of each token, we can bring down the number of features to 27,271, as seen in the preceding output — only about a third of the original features. Let’s look at some tokens again:

In:

feature_names = vect.get_feature_names()

print("First 50 features:\n{}".format(feature_names[:50]))

print("Features 20010 to 20030:\n{}".format(feature_names[20010:20030]))

print("Every 700th feature:\n{}".format(feature_names[::700]))

Out:

First 50 features:

['00', '000', '007', '00s', '01', '02', '03', '04', '05', '06', '07', '08',

'09', '10', '100', '1000', '100th', '101', '102', '103', '104', '105', '107',

'108', '10s', '10th', '11', '110', '112', '116', '117', '11th', '12', '120',

'12th', '13', '135', '13th', '14', '140', '14th', '15', '150', '15th', '16',

'160', '1600', '16mm', '16s', '16th']

Features 20010 to 20030:

['repentance', 'repercussions', 'repertoire', 'repetition', 'repetitions',

'repetitious', 'repetitive', 'rephrase', 'replace', 'replaced', 'replacement',

'replaces', 'replacing', 'replay', 'replayable', 'replayed', 'replaying',

'replays', 'replete', 'replica']

Every 700th feature:

['00', 'affections', 'appropriately', 'barbra', 'blurbs', 'butchered',

'cheese', 'commitment', 'courts', 'deconstructed', 'disgraceful', 'dvds',

'eschews', 'fell', 'freezer', 'goriest', 'hauser', 'hungary', 'insinuate',

'juggle', 'leering', 'maelstrom', 'messiah', 'music', 'occasional', 'parking',

'pleasantville', 'pronunciation', 'recipient', 'reviews', 'sas', 'shea',

'sneers', 'steiger', 'swastika', 'thrusting', 'tvs', 'vampyre', 'westerns']

There are clearly many fewer numbers, and some of the more obscure words or misspellings seem to have vanished. Let’s see how well our model performs by doing a grid search again:

In:

grid = GridSearchCV(LogisticRegression(), param_grid, cv=5)

grid.fit(X_train, y_train)

print("Best cross-validation score: {:.2f}".format(grid.best_score_))

Out:

Best cross-validation score: 0.89

The best validation accuracy of the grid search is still 89%, unchanged from before. We didn’t improve our model, but having fewer features to deal with speeds up processing and throwing away useless features might make the model more interpretable.

Note: If the transform method of CountVectorizer is called on a document that contains words that were not contained in the training data, these words will be ignored as they are not part of the dictionary. This is not really an issue for classification, as it’s not possible to learn anything about words that are not in the training data. For some applications, like spam detection, it might be helpful to add a feature that encodes how many so-called “out of vocabulary” words there are in a particular document, though. For this to work, you need to set min_df; otherwise, this feature will never be active during training