A main drawback of decision trees is that they tend to overfit the training data. Random forests are one way to address this problem. A random forest is essentially a collection of decision trees, where each tree is slightly different from the others, usually trained with the “bagging” method. The general idea of the bagging method is that a combination of learning models increases the overall result. The idea behind this is that each tree might do a relatively good job of predicting, but will likely overfit in different ways, we can reduce the amount of overfitting by averaging their results.

How to build a Random Forest?

First of all, you need to decide the number of trees to build (the n_estimators parameter). These trees will be built completely independently from each other, and the algorithm will make different random choices for each tree to make sure the trees are distinct.

1. Build a Random Bootstrap sample for each tree

Assume that our data has \(N\) samples. To build a tree, we first take what we called a bootstrap sample of our data. We build a dataset with \(N\) samples, randomly chosen, with replacement, from the original dataset. This will create a dataset that is a big as the original dataset, but some data points will be missing from it, and some will be repeated.

2. Grow each decision tree from the bootstrap sample

In each node the algorithm randomly selects \(k\) features from total \(m\) features without replacement, where \(k << m\). The number of features that are selected is controlled by the max_features parameter. This selection of a subset of features is repeated in each node, so that each node in a tree can make a decision using a different subset of the features.

Split the node using the feature that provides the best split according to the objective function, for instance, by maximizing the information gain.

The bootstrap sampling leads to each decision tree (1) in the random forest being built on a slightly different dataset. Because of the selection of features in each node, each split in each tree operates on a different subset of features (2). Together, these two mechanisms ensure that all the trees in the random forest are different.

A critical parameter in this process is max_features. If we

- set max_features to n_features, that means that each split can look to all features in the dataset, and no randomness will be injected in the feature selection (the randomness due the bootstrapping remains, though).

- set max_features to \(1\), that means that the splits have no choice at all on which feature to test, and can only search over different thresholds for the feature that was selected randomly.

- set a high max_features means that the trees in the random forest will be quite similar, and they will be able to fit the data easily, using the most distinctive features.

- set a low max_features means that the trees in the random forest will be quite different, and that each tree might need to be very deep in order to fit the data well.

Prediction

To make a prediction, the algorithm first makes a prediction for every tree in the forest. For regression, we can average these results to get our final prediction. For classification, a “soft voting” strategy is used. This means each tree makes a “soft” prediction, providing a probability for each possible output label. The probabilities predicited by all the treess are averaged, and the class with the highest probability is predicted.

Analyzing an example

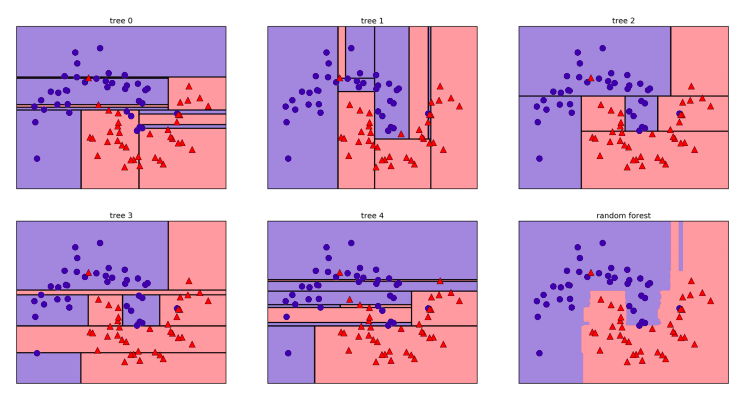

Considering a random forest of five trees to the two_moons dataset

In:

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.datasets import make_moons

X, y = make_moons(n_samples=100, noise=0.25, random_state=3)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, stratify=y,

random_state=42)

forest = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=5, random_state=2)

forest.fit(X_train, y_train)

Let’s visualize the decision boundaries learned by each tree, together with their aggregate prediction as made by the forest.

You can clearly see that the decision boundaries learned by the five trees are quite different. Each of them makes some mistakes, as some of the training points that are plotted here were not actually included in the training sets of the trees, due to the bootstrap sampling.

The random forest overfits less than any of the trees individually, and provides a much more intuitive decision boundary. In any real application, we would use many more trees (often hundreds or thousands), leading to even smoother boundaries.

We could adjust the max_features setting, or apply pre-pruning as we did for the single decision tree. However, often the default parameters of the random forest already work quite well.

Similarly to the decision tree, the random forest provides feature importances, which are computed by aggregating the feature importances over the trees in the forest. Typically, the feature importances provided by the random forest are more reliable than the ones provided by a single tree.

Strenghts, Weaknesses, and Parameters

Random forests for regression and classification are currently among the most widely used machine learning methods. They are very powerful, often work well without heavy tuning of the parameters, and don’t require scaling of the data.

While building random forests on large datasets might be somewhat time consuming, it can be parallelized across multiple CPU cores within a computer easily. If you are using a multi-core processor, you can use the n_jobs parameter to adjust the number of cores to use. Using more CPU cores will result in linear speed-ups (using two cores, the training of the random forest will be twice as fast), but specifying n_jobs larger than the number of cores will not help. You can set \(n\_jobs=-1\) to use all the cores in your computer.

You should keep in mind that random forests, by their nature, are random, and setting different random states (or not setting the random_state at all) can drastically change the model that is built. The more trees there are in the forest, the more robust it will be against the choice of random state. If you want to have reproducible results, it is important to fix the random_state.

Random forests don’t tend to perform well on very high dimensional, sparse data, such as text data. For this kind of data, linear models might be more appropriate. Random forests usually work well even on very large datasets, and training can easily be parallelized over many CPU cores within a powerful computer. However, random forests require more memory and are slower to train and to predict than linear models. If time and memory are important in an application, it might make sense to use a linear model instead.

The important parameters to adjust are n_estimators, max_features, and possibly pre-pruning options like max_depth. For n_estimators, larger is always better. Averaging more trees will yield a more robust ensemble by reducing overfitting. However, there are diminishing returns, and more trees need more memory and more time to train. A common rule of thumb is to build “as many as you have time/memory for”.

As described earlier, max_features determines how random each tree is, and a smaller max_features reduces overfitting. In general, it’s a good rule of thumb to use the default values: \(max\_features=\sqrt{n\_features}\) for classification and \(max\_features=log_2(n\_features)\) for regression. Adding max_features or max_leaf_nodes might sometimes improve performance. It can also drastically reduce space and time requirements for training and prediction.